03

Mar, 2010

03

Mar, 2010

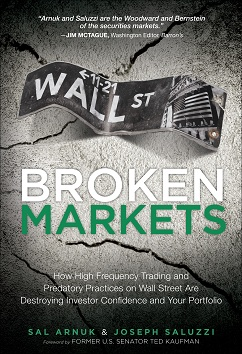

Read This HFT-related-Market-Structure-Abuse Commentary from Senator Kaufman

We were mentioned in his commentary, and we are honored to have been so.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sen-ted-kaufman/concerned-about-stock-mar_b_484230.html

March 3, 2010

Concerned about Stock Market Abuses? Join the Club

I have spoken on the Senate floor many times about the importance of transparency in our markets. Without transparency, there is little hope for effective regulation. And without effective regulation, the very credibility of our markets is threatened.

But I am concerned recent changes in our markets have outpaced regulatory understanding and, accordingly, pose a threat to the stability and credibility of our equities markets. Chief among these is high frequency trading.

Over the past few years, the daily volume of stocks trading in microseconds — the hallmark of high frequency trading — has exploded from 30 to 70 percent of the U.S. market. Money and talent are surging into a high frequency trading industry that is red hot, expanding daily into other financial markets not just in the United States but in global capital markets as well.

High frequency trading strategies are pervasive on today’s Wall Street, which is fixated on short-term trading profits. Thus far, our regulators have been unable to shed much light on these opaque and dark markets, in part because of their limited understanding of the various types of high frequency trading strategies. Needless to say, I’m very worried about that.

Last year, I felt a little lonely raising these concerns. But this year, I’m starting to have plenty of company.

On January 13th, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a 74-page concept release to solicit comments on a wide-range of market structure issues. The document raised a number of important questions about the current state of our equities markets, including: “Does implementation of a specific [high frequency trading] strategy benefit or harm market structure performance and the interests of long-term investors?”

The SEC also called attention to trading strategies that are potentially manipulative, including momentum ignition strategies in which “the proprietary firm may initiate a series of orders and trades (along with perhaps spreading false rumors in the marketplace) in an attempt to ignite a rapid price move either up or down.”

The SEC went on to ask, “Does…the speed of trading and ability to generate a large amount of orders across multiple trading centers render this type of strategy more of a problem today?”

The SEC raised many critical questions in its concept release, and I appreciate that the SEC is trying to undertake a baseline review. As its comment period moves forward, I am pleased to report that other regulators and market participants, both at home and abroad, have taken notice of the global equity markets’ recent changes, including the rise in high frequency trading.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, in the March 2010 issue of its Chicago Fed Letter, argued that the rise of high frequency trading constitutes a systemic risk, asserting, “The high frequency trading environment has the potential to generate errors and losses at a speed and magnitude far greater than that in a floor or screen-based trading environment.” In other words, high frequency trading firms are currently locked into a technological arms race that may result in some big disasters.

Citing a number of instances in which trading errors have occurred, the Chicago Fed stated that “a major issue for regulators and policymakers is the extent to which high frequency trading, unfiltered sponsored access, and co-location amplify risks, including systemic risk, by increasing the speed at which trading errors or fraudulent trades can occur.”

Moreover, the letter cautions us about the potential for future high frequency trading errors, arguing, “Although algorithmic trading errors have occurred, we likely have not yet seen the full breadth, magnitude, and speed with which they can be generated.”

There is action internationally as well. On February 4th, Great Britain’s Financial Services Secretary, Paul Myners, announced that British regulators were also conducting an ongoing examination of high frequency trading practices, stating, “People are coming to me, both market users and intermediaries, saying that they have concerns about high frequency trading.”

This development comes on the heels of another British effort targeting so-called “spoofing” or “layering” strategies in which traders feign interest in buying or selling a stock in order to manipulate its price. In order to deter such trading practices, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) announced that it would fine or suspend participants who engage in market manipulation. Noting that some market participants may not be sure that spoofing or layering is wrong, an FSA spokeswoman said, “This is to clarify that it is.”

In Australia, market participants are also requesting clearer definitions of market manipulation, particularly with regard to momentum strategies like spoofing. In a review of algorithmic trading published February 8th, the Australian Securities Exchange called on its regulators to, “Ensure that…market manipulation provisions…are adequately drafted to capture contemporary forms of trading and provide a more granular definition of market manipulation.”

It is critical our regulators understand the risks posed by high frequency trading, both in terms of manipulation and on a systemic level. As the Chicago Fed stated, the threat of an algorithmic trading error wreaking havoc on our equities markets is only magnified by so-called “naked,” or unfiltered sponsored access arrangements, which allow traders to interact on markets directly — without being subject to standard pre-trade filters or risk controls.

Robert Colby, the former deputy director of the SEC’s Division of Trading and Markets, warned last September that naked access leaves the marketplace vulnerable to faulty algorithms. In a speech given at a forum on the future of high frequency trading, which was cited by the Chicago Federal Reserve’s recent letter, Mr. Colby stated that hundreds of thousands of trades representing billions of dollars could occur in the two minutes it could take for a broker-dealer to cancel an erroneous order executed through naked access.

According to a report released December 14th by the research firm Aite Group, naked access now accounts for a staggering 38% of the market’s average daily volume compared to 9% only four years ago.

Let me reiterate that: almost forty percent of the market’s volume is executed by high frequency traders interacting directly on exchanges without being subject to any pre-trade risk monitoring.

In January, the SEC acted to address this ominous trend by proposing mandatory pre-trade risk checks for those participating in sponsored access arrangements. This move would essentially eliminate naked access, and I applaud the SEC for its proposal.

While I am pleased that the SEC has taken on naked access and has issued a concept release on market structure issues, there is much work that still needs to be done in order to gain a better understanding of high frequency trading strategies and the risks of frontrunning and manipulation they may create. In the last few months, several industry studies aimed at defining the benefits and drawbacks of high frequency trading have emerged. While these studies may not be the equivalent of peer-reviewed academic studies, they do have the credibility of real-world market experts. And they begin to shed light on the opaque and largely unregulated high frequency trading strategies that dominate today’s marketplace.

In addition to the Aite Group study, reports by the research firm, Quantitative Services Group (QSG), the investment banking firm, Jefferies Company, and the institutional brokerage firm, Themis Trading, all raise troubling concerns about the costs of high frequency trading to investors and reinforce the need for enhanced regulatory oversight of these trading practices.

Last November, QSG analyzed the degree to which orders placed by institutional investors are vulnerable to high frequency predatory traders who sniff out large orders and trade ahead of them.

Specifically, the study concluded investors placing large orders risk, “leaving a statistical footprint that can be exploited by the ‘tape reading’ HFT algorithms.” While traders have long tried to trade ahead of large institutional orders, they now have the technology and models to make an exact science out of it.

In a study put forth on November 3rd, the Jefferies Company estimated high frequency traders gain a 100 to 200 millisecond advantage by co-locating their computer servers next to exchanges and subscribing directly to market data feeds. As a result, Jefferies concludes, high frequency traders enjoy, “(almost) risk-free arbitrage opportunities.”

A Themis Trading white paper released in December elaborated on Jefferies’ conclusion, asserting that high frequency traders, “know with near certainty what the market will be milliseconds ahead of everybody else.”

The studies and papers I have mentioned underscore the need for the SEC to implement stricter reporting and disclosure requirements for high frequency traders under its “large trader” authority, as Chairman Mary Schapiro promised she would in a letter to me on December 3rd. We need tagging of high frequency trading orders and next day disclosure to the regulators, and we need it now.

For investors to have confidence in the credibility of our markets, regulators must vigorously pursue a robust framework that maintains strong, fair and transparent markets. I would make five points along these lines.

First, the regulators must get back in the business of providing guidance to market participants on acceptable trading practices and strategies. While the formal rule-making process is a critical component of any robust regulatory framework, so too are timely guidelines that bring clarity and stability to the marketplace. Co-location, flash orders and naked access are just a few practices that seem to have entered the market and become fairly widespread before being subject to proper regulatory scrutiny. For our markets to be credible, it is vital that regulators be pro-active, rather than reactive, when future developments arise.

Second, the SEC must gain a better understanding of current trading strategies by using its “large trader” authority to gather data on high frequency trading activity. Just as importantly, this data – once masked – should be made available to the public for others to analyze.

I am concerned that academics and other independent market analysts do not have access to the data they need to conduct empirical studies on the questions raised by the SEC in its concept release. Absent such data, the ongoing market structure review predictably will receive mainly self-serving comments from high frequency traders themselves and from other market participants who compete for high frequency volume and market share.

Evidence-based rule-making should not be a one-way ratchet because all the “evidence” is provided by those whom the SEC is charged with regulating. We need the SEC to require tagging and disclosure of high frequency trades so that objective and independent analysts — at FINRA, in academia or elsewhere — are given the opportunity to study and discern what effects high frequency trading strategies have on long-term investors; they can also help determine which strategies should be considered manipulative.

Third, regulators must better define manipulative activity and provide clear guidance for traders to follow, just as Britain’s regulators have done in the area of spoofing. By providing “rules of the road,” regulators can create a system better able to prevent and prosecute manipulative activity.

Fourth, the SEC must continue to make reducing systemic and operational risk a top regulatory priority. The SEC’s proposal on naked access is a good first step, but exchanges must also be directed to impose universal pre-trade risk checks. If left solely in the hands of individual broker-dealers, a race to the bottom might ensue. We simply must have a level playing field when it comes to risk management that protects our equities markets from fat fingers or faulty algorithms. Regulators must therefore ensure that firms have appropriate operational risk controls to minimize the incidence and magnitude of such errors while also preventing a tidal wave of copycat strategies from potentially wreaking havoc in our equities markets.

Fifth, the SEC should act to address the burgeoning number of order cancellations in the equities markets. While cancellations are not inherently bad – potentially enhancing liquidity by affording automated traders greater flexibility when posting quotes – their use in today’s marketplace is clearly excessive and virtually a prima facie case that battles between competing algorithms, which use cancelled orders as feints and indications of misdirection, have become all-too-commonplace, overloading the system and regulators alike.

According to the high frequency trading firm T3Live, on a recent trading day, only 1.247 billion of the 89.704 billion orders on Nasdaq’s book were executed – meaning a whopping 98.6% of the total bids and offers were not filled. Cancellations by high frequency traders, according to T3Live, were responsible for the bulk of these unfilled orders.

The high frequency traders that create such massive cancellation rates might cause market data costs for investors to rise, make the price discovery process less efficient and complicate the regulators’ understanding of continuously evolving trading strategies. What’s more, some manipulative strategies, including layering, rely on the ability to rapidly cancel orders in order to profit from changes in price.

Perhaps excessive cancellation rates should carry a charge. If traders exceed a specified ratio of cancellations to orders, it’s only fair that they pay a fee. The ratio could be set high enough so that it would not affect long-term investors (even day traders), and should apply to all trading platforms, including dark pools and ATSs as well as exchanges.

The high-frequency traders who rely on massive cancellations are using up more bandwidth and putting more stress on the data centers. Attempts to reign in cancellations or impose charges are not without precedent. In fact they have already been implemented in derivatives markets where overall volume is a small fraction of the volume in the cash market for stocks. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s volume ratio test and the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange’s bandwidth usage policy both represent attempts to reign in excessive cancellations and might provide a helpful model for regulators wishing to do the same.

Finally, the high frequency trading industry must come to the table and play a constructive role in resolving current issues in the marketplace, including preventing manipulation and managing risk. In order to maintain fair and transparent markets and avoid unintended consequences, market participants from across the industry must contribute to the regulatory process. I am pleased that a number of responsible firms are stepping forward in a constructive way, both in educating the SEC and me and my staff. I look forward to continuing to work with these industry players.

We all must work together, in the interests of liquidity, efficiency, transparency and fairness to ensure our markets are the strongest and best-regulated in the world. But we cannot have one without the other — for markets to be strong, they must be well-regulated. So with this reality in mind, I look forward to working with my colleagues, regulatory agencies, and people from across the financial industry to ensure our markets are free, credible and the envy of the world.