28

Sep, 2021

28

Sep, 2021

Market Makers Lose at Their Own Game

The SEC just charged two defendants in a wash trading scheme that was devised based on maker-taker pricing model. The scheme was hatched after one of the defendants (“Gu”) was watching the February 18th US House Financial Services Committee “Meme Stock” hearing and he heard the CEO of “Broker-dealer B” (Vlad Tenev, Robinhood) testify that broker-dealer B “pioneered commission free and zero contract fee options trading”.

The scheme basically came down to this: “If I could trade options for free through one broker and collect a rebate from another broker, then I may have created a money machine”.

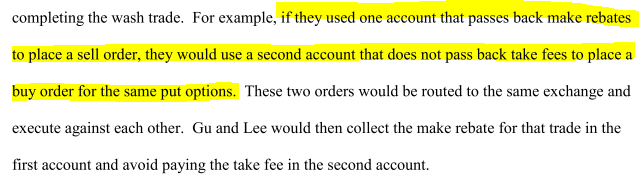

Gu realized that, even though he was a retail customer, he could collect a rebate for posting liquidity because some brokers like Interactive Brokers passed the rebates back to the customer. He also realized that he could take liquidity for free because he could trade with another broker like Robinhood who didn’t pass back take fees. Robinhood and some other zero-commission retail brokers don’t pass back take fees since they route all their orders to market makers who pay for those orders. According to the SEC:

But how was Gu able to trade with his own orders without a market maker taking the other side of the trade?

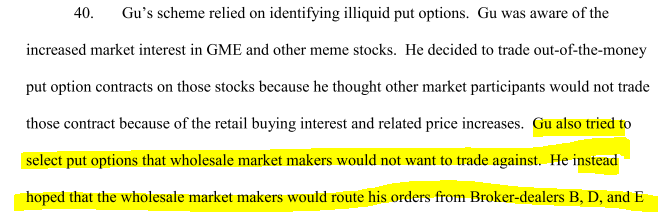

In other words, if he placed an order to sell at $0.50, and then place a buy order at $0.50, normally a market maker would “provide liquidity” and step ahead of the sell order and offer some very small price improvement. Market maker liquidity would ruin this scam since Gu would not be trading with himself and therefore would not be collecting the rebate. Why did the scheme work then? How did the defendants trade over 3 million option contracts and make over $700,000 in gains in less than a month? The key was trading option contracts that they thought market makers wouldn’t take the other side of:

If Gu made over $700k and the brokers still took their cut, then who lost money?

The market makers were the losers since they received the orders from the retail brokers and chose not to take the other side. Instead, they routed the orders to the exchange and incurred a take fee. Since this fee was most likely not passed back to the zero-commission broker, the market maker had to eat it. And to add insult to injury, they actually lost even more money since they likely paid for the order flow.

This wash trading scheme was not small which is why it probably quickly attracted the attention of the market makers who alerted the brokers who then quickly froze the defendants accounts. How big was Gu compared to the overall market for some of these options? The SEC noted that on just one day, March 4th, they represented 60-80% of all put options traded in some MEME stocks:

Our Thoughts

This case is a great example of why the payment for order flow debate should not just focus on market maker payments. Exchange rebates also cause order routing conflicts and should be considered in any market structure overhaul discussion. Routing through various brokers to take advantage of different commission pricing models should have no place in our markets. The trades involved in this wash trading scam added nothing to the price discovery process and in fact they likely distorted this process.

As we wait for the much-anticipated SEC report on their findings about the “MEME stock” saga, most of the speculation has revolved around whether or not the SEC will propose a ban on payment for order flow. We doubt very much that the SEC will propose elimination of market maker payments, but we do think they might question the entire maker-taker system. Chair Gensler has already said that our market structure, which hasn’t had a revamp in 15 years, is due for an overhaul. This case disproves the argument that “the market has never been better for retail investors”. There are inherent conflicts of interests that are buried deep in our market structure that need to be addressed.